Orange Juice

Your

quarterly

vitamin.

Absurdity in Advertising

Written on 02/23/16 5:13 PM

by Dan Henrick

Now that it’s been a few weeks since the Super Bowl, we’re finally able to get an objective look at how each of this year’s commercials resonated with viewers. According to Advertising Age, the big winner was Mountain Dew’s “PuppyMonkeyBaby” spot, a bizarre and somewhat divisive ad that nevertheless dominated Facebook and Twitter in the days since. Another popular ad, Heinz’s “Wiener Stampede” performed well, and elicited an overwhelmingly positive sentiment among viewers polled. Both of these spots capitalize on heightened absurdism, a direction which has become increasingly prevalent among ads aimed at young males. Although the voice of these ads appears to be quite modern, the history behind this comedic direction is older, and by understanding its history and methodology, we can understand why it resonates so strongly. In fact, the first clear progenitor of absurdism just turned 100 years old this month.

On February 5th, 1916, the Café Voltaire opened in Zurich, Switzerland. The founder, Tristan Tzara, along with a number of exiled artists, were at the vanguard of the artistic movement known as Dada. While Switzerland was technically a neutral country during World War I, these writers, poets, painters, and dancers (many of them refugees) were still inundated with images and news of the War’s tremendous loss of life. To them, the only reasonable response to the senseless horror around them was “nonsense.” According to Tzara’s manifesto, art must imitate life, but if life is random, nihilistic and pointless, then art should be every bit as pointless and absurd.

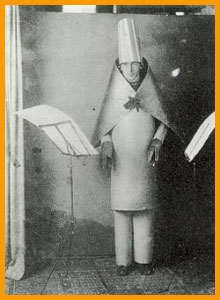

That is not to say that the existential dread that birthed the Dada movement is humorless one. If anything, it was completely the opposite. Dada performances were often raucous, spirited shows that mocked war and society, but also mundane every day trivialities. I mean, take a look at this photo of poet Hugo Ball in a full robot costume, and you get a sense of what a Dada show was like.

Like any movement borne out of such a volatile environment, Dadaism quickly imploded in Zurich. The creators behind it splintered off to what we now call Surrealism, Futurism, and Cubism, all influential in their own right.

So, why are we still talking about a short-lived bohemian fad in Switzerland 100 years later? And moreover, why should we care? The answer is that Dada’s DNA is still pervasive throughout modern humor, philosophy, and especially marketing. Much of that is due to the hugely influential comedy pioneers, Monty Python’s Flying Circus, who directly credited their specific absurd comedic voice to their exposure to Dadaism.

In recent years, studies have shown that messages delivered with an absurd voice not only resonate stronger with audiences than appeals to class status or sex appeal, but they also resonate across cultures. Since the morals and social norms of different cultures vary from region to region, much can be lost in translation. However, with absurdism, the “nonsense” or tweaking of everyday commonalities, the message is universal.

The logic behind this is fairly simple. If you shock a viewer with a bizarre or nonsensical image and then twist that image to connect with a familiar experience or emotion in an unexpected way, that connection will be stronger than a direct appeal. A study published in the Journal of Promotion Management showed that this is true across cultures and genders. That initial jolt causes the viewer to pay attention, and not only will they be able to recall the message, but they will retain more of the message itself.

There are caveats to this approach, though. For example, if that connection between the absurd and the every day is too tenuous, then you risk alienating your audience or preventing them from recalling your message or product entirely. Also, this study also found that while absurdism is one of the most effective ways to imprint your message across genders and cultures, that doesn’t necessarily translate to “persuasiveness.” In fact, viewers who identify as masculine and individualistic are more likely to respond positively to an absurdist message than viewers who either identify as feminine or collectivist. Hence, that is why advertisements like Mountain Dew’s “PuppyMonkeyBaby” is so effective in targeting young men.

It would be hard to tell what Tristan Tzara would think of the influence of Dada on today’s culture. On one hand, he was an outspoken liberal political voice who protested France’s actions in the Algerian War. On the other hand, he was also a gregarious showman and well-known promoter who relished the attention. Either way, the echoes of Tzara and his contemporaries’ message, that sometimes the best way to deliver a truth is through nonsense, still resonates today.